Markov Models and $$n$$-grams

Models like linear/ logistic regression, multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) operate on fixed-length input (tabular or image data) without sequential structure. What is a sequential data? Tasks like video analysis, time-series prediction, image captioning, speech synthesis, and translation involve sequentially structured inputs and outputs, requiring specialized models.

Introduction

RNNs are designed to capture the dynamics of sequences through recurrent connections that pass information across adjacent time steps. Recurrent neural networks are unrolled across time steps (or sequence steps), with the same underlying parameters applied at each step.

RNNs have achieved breakthroughs in tasks like handwritting recognition, translation, and medical diagosis but have been partly replaced by Transformer models.

Working with Sequences

Shift in Perspective Traditional models work with a single feature vector \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\). Sequence models handle ordered lists of feature vectors: \(\mathbf{x}_{1}, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_{T}\), where each vector \(\mathbf{x}_{t} \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\) is indexed by time step \(t \in \mathbb{Z}^{+}\).

Sequential Data Some datasets consist of one long sequence (e.g., climate sensor data), sampled into subsequences of length \(T\).

More commonly, data arrive as multiple sequences (e.g., documents, patient stays), where each sequence has its own length \(T_{i}\).

Unlike independent feature vectors, elements within a sequence are dependent:

- Later words in a document depend on earlier ones.

- A patient’s medication depends on prior events.

Sequential Dependence Sequences reflect patterns that make auto-fill features and predictions possible.

Sequences are modeled as samples from a fixed underlying distribution over entire sequences, \(P(X_{1}, \dots, X_{T})\), rather than assuming independence or stationarity.

Examples of Sequential Tasks

- Fixed input to fixed target: Predict a label \(y\) from a sequence (e.g., sentiment classification).

- Fixed input to sequential target: Predict \((y_{1}, \ldots, y_{T})\) from an input (e.g., image captioning).

- Sequential input to sequential target:

- Aligned: Input at each step aligns with the target (e.g., part-of-speech tagging).

- Unaligned: No step-wise correspondence (e.g., machine translation).

Sequence Modeling The simplest task is unsupervised density modeling: Estimate \(p(\mathbf{x}_{1}, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_{T})\), the likelihood of a sequence, where the probability reflects the joint likelihood of the sequence elements based on their relationships. This is useful for understanding and generating sequences.

Autoregressive Models

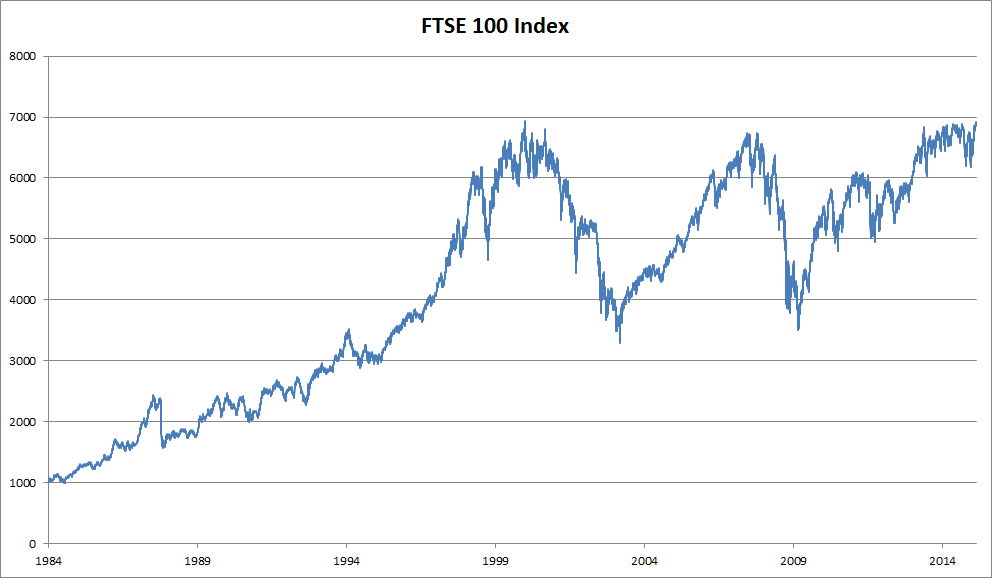

Sequence Data Autoregressive models analyze sequentially structured data. Consider stock prices like those in the FTSE 100 index: \(x_t, x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1,\) where each \(x_t\) represents the price at time \(t\). The goal is to predict the next value \(x_t\) based on its history.

Modeling Sequential Data Given a sequence, the trader wants to estimate the conditional distribution:

\[P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1),\]focusing on key statistics like the expected value:

\[\mathbb{E}[x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1].\]Autoregressive models perform this task by regressing \(x_t\) onto previous values \(x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1\). However, the challenge lies in the variable input size, as the number of inputs grows with \(t\).

Strategies for Fixed-Length Inputs

-

Windowing: Instead of using the full history, consider only a window of size \(\tau\):

\[x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_{t-\tau}.\]This reduces the number of inputs to a fixed size for \(t > \tau\), enabling the use of models like linear regression or neural networks.

-

Latent State Representations: Maintain a latent summary \(h_t\) of past observations.

-

Predict \(x_t\) using: \(\hat{x}_t = P(x_t \mid h_t).\)

-

Update the latent state with: \(h_t = g(h_{t-1}, x_{t-1}).\)

This approach creates latent autoregressive models, as \(h_t\) is not directly observed.

-

Training Data and Stationarity Training data is often constructed by sampling fixed-length windows from historical data. Even though the specific values \(x_t\) may change, the underlying generation process is often assumed to be stationary, meaning the dynamics of \(P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1)\) remain consistent over time.

Sequence Models

Joint Probability of Sequences Sequence models estimate the joint probability of an entire sequence, typically for data composed of discrete tokens like words. These models are often referred to as language models when dealing with natural language data. Language models are particularly useful for:

- Evaluating the likelihood of sequences (e.g., comparing naturalness of sentences in machine translation or speech recognition).

- Sampling sequences and optimizing for the most likely outcomes.

The joint probability of a sequence \(P(x_1, \ldots, x_T)\) can be decomposed using the chain rule of probability into conditional densities:

\[P(x_1, \ldots, x_T) = P(x_1) \prod_{t=2}^T P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1).\]For discrete signals, the model must act as a probabilistic classifier, outputting a distribution over the vocabulary for the next word based on the leftward context.

Markov Models

Instead of conditioning on the entire history \(x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1\), we may limit the context to the previous \(\tau\) time steps (without any loss in predictive power), i.e., \(x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_{t-\tau}\). This is known as the Markov condition, where the future is conditionally independent of the past given the recent history. When:

- \(\tau = 1\), it is called a first - order Markov model.

- \(\tau = k\), it is called a \(k^{th}\) - order Markov model.

For a first-order Markov model, the factorization simplifies to:

\[P(x_1, \ldots, x_T) = P(x_1) \prod_{t=2}^T P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}).\]Markov models are practical even if the condition is not strictly true. With real-world text, additional context improves predictions, but the marginal benefits diminish as the context length increases. Hence, many models rely on the Markov assumption for computational efficiency.

For discrete data like language, Markov models estimate \(P(x_t \mid x_{t-1})\) via relative frequency counts and efficiently compute the most likely sequence using dynamic programming.

The Order of Decoding

The factorization of a sequence can follow any order (e.g., left-to-right or right-to-left):

-

Left-to-right (natural reading order):

\[P(x_1, \ldots, x_T) = P(x_1) \prod_{t=2}^T P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1).\] -

Right-to-left:

\[P(x_1, \ldots, x_T) = P(x_T) \prod_{t=T-1}^1 P(x_t \mid x_{t+1}, \ldots, x_T).\]

While all orders are mathematically valid, left-to-right decoding is preferred for several reasons:

- Naturalness: Matches the human reading process.

-

Incrementality: Probabilities over sequences can be extended by multiplying by the conditional probability of the next token:

\[P(x_{t+1}, \ldots, x_1) = P(x_{t}, \ldots, x_1) \cdot P(x_{t+1} \mid x_{t}, \ldots, x_1).\] - Predictive Power: Predicting adjacent tokens is often more feasible than predicting tokens at arbitrary positions.

- Causal Relationships: Forward predictions (e.g., \(P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t)\)) often align with causality, whereas reverse predictions (\(P(x_t \mid x_{t+1})\)) are generally infeasible. Future does not affect present.

For instance, in causal systems, forward predictions might follow:

\[x_{t+1} = f(x_t) + \epsilon,\]where \(\epsilon\) represents additive noise. The reverse relationship generally does not hold.

For a more detailed exploration of causality and sequence modeling, refer to Elements of Causal Inference.

Converting Raw Text into Sequence Data

To make sure the input machine readable we have to do the following:

- Load text as strings into memory.

- Split the strings into tokens (e.g., words or characters).

- Build a vocabulary dictionary to associate each vocabulary element with a numerical index.

- Convert the text into sequences of numerical indices.

To learn more about this, please read [9.2. Converting Raw Text into Sequence Data]. The chapter is really straightforward and should have no confusion.

Language Models

Language models play a crucial role in natural language processing and generation tasks. For example, an ideal language model could generate coherent and natural text by sequentially sampling tokens according to their conditional probabilities:

\[x_t \sim P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1).\]In such a scenario, every token generated would resemble natural language, such as grammatically correct English. This capability would enable the model to engage in meaningful dialogue simply by conditioning its output on previous dialogue fragments. However, achieving this goal would require a model to not only generate syntactically correct text but also understand the underlying context and meaning, a challenge that remains unresolved.

Practical Applications Despite their limitations, language models offer immense utility in various tasks, such as:

-

Speech Recognition: Ambiguities in phonetically similar phrases, such as “to recognize speech” and “to wreck a nice beach,” can be resolved by a language model. The model assigns higher probabilities to plausible interpretations, filtering out nonsensical outputs.

-

Document Summarization: Knowing the frequency and naturalness of phrases, a language model can differentiate between:

- “Dog bites man” (common) and “Man bites dog” (rare).

- “I want to eat grandma” (alarming) and “I want to eat, grandma” (benign).

Language models enable systems to make contextually appropriate and semantically meaningful decisions, improving the quality of machine-generated language outputs.

Learning Language Models

To model a document or a sequence of tokens, we start with the basic probability rules. Suppose we tokenize text data at the word level. The joint probability of a sequence of tokens \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_T\) can be expressed as:

\[P(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_T) = \prod_{t=1}^T P(x_t \mid x_1, \ldots, x_{t-1}).\]For instance, the probability of the sequence “deep learning is fun” can be written as:

\[\begin{aligned} P(\textrm{deep}, \textrm{learning}, \textrm{is}, \textrm{fun}) = & \, P(\textrm{deep}) \cdot P(\textrm{learning} \mid \textrm{deep}) \\ & \cdot P(\textrm{is} \mid \textrm{deep}, \textrm{learning}) \cdot P(\textrm{fun} \mid \textrm{deep}, \textrm{learning}, \textrm{is}). \end{aligned}\]Markov Models and \(n\)-grams

By applying Markov models, we approximate sequence modeling using limited dependencies. A first-order Markov property assumes that:

\[P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t, \ldots, x_1) = P(x_{t+1} \mid x_t).\]This allows us to simplify sequence probabilities. For example:

\[\begin{aligned} P(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4) & = P(x_1) P(x_2) P(x_3) P(x_4), \\ P(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4) & = P(x_1) P(x_2 \mid x_1) P(x_3 \mid x_2) P(x_4 \mid x_3), \\ P(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4) & = P(x_1) P(x_2 \mid x_1) P(x_3 \mid x_1, x_2) P(x_4 \mid x_2, x_3). \end{aligned}\]These approximations correspond to unigram, bigram, and trigram models, respectively. Note that such probabilities are language model parameters.

Word Frequency

Using a large training dataset (e.g., Wikipedia or Project Gutenberg), we estimate probabilities based on word frequencies. For example:

\[\hat{P}(\textrm{deep}) = \frac{\text{count}(\textrm{deep})}{\text{total words}},\]and for word pairs:

\[\hat{P}(\textrm{learning} \mid \textrm{deep}) = \frac{\text{count}(\textrm{deep, learning})}{\text{count}(\textrm{deep})}.\]However, estimating probabilities for rare word combinations becomes challenging as data sparsity increases.

Laplace Smoothing

To handle data sparsity, we use Laplace smoothing, adding a small constant \(\epsilon\) to all counts:

\[\begin{aligned} \hat{P}(x) & = \frac{n(x) + \epsilon/m}{n + \epsilon}, \\ \hat{P}(x' \mid x) & = \frac{n(x, x') + \epsilon \hat{P}(x')}{n(x) + \epsilon}, \\ \hat{P}(x'' \mid x, x') & = \frac{n(x, x', x'') + \epsilon \hat{P}(x'')}{n(x, x') + \epsilon}. \end{aligned}\]Here, \(n\) is the total number of words in the training set, \(m\) is the number of unique words and \(\epsilon\) determines the degree of smoothing, where \(\epsilon = 0\) means no smoothing and \(\epsilon \to \infty\) approximates a uniform distribution.

Challenges with \(n\)-grams \(n\)-gram models face issues such as large storage requirements, inability to capture word meaning (e.g., “cat” and “feline”), and poor performance on novel sequences. Deep learning models address these shortcomings by learning contextual representations and generalizing better to unseen data.

Perplexity

A good language model is able to predict, with high accuracy, the tokens that come next.

- “It is raining outside”

- “It is raining banana tree”

- “It is raining piouw;kcj pwepoiut”

Perplexity measures how well a language model predicts a sequence. Given a sequence of \(n\) tokens, the cross-entropy loss averaged over the sequence is:

\[\frac{1}{n} \sum_{t=1}^n -\log P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1).\]The perplexity is defined as the exponential of the average cross-entropy:

\[\exp\left(-\frac{1}{n} \sum_{t=1}^n \log P(x_t \mid x_{t-1}, \ldots, x_1)\right).\]Interpretations:

- Best Case: The model predicts \(P(x_t) = 1\) for all tokens. Perplexity = 1.

- Worst Case: The model predicts \(P(x_t) = 0\) for some token. Perplexity = infinity.

- Baseline: For uniform probability distribution over \(m\) tokens, perplexity = \(m\).

Lower perplexity indicates a better language model.

Partitioning Sequences

Language models process minibatches of sequences (assumption; question, how to read minibatches of input sequences and target sequences at random?). Suppose we have a dataset of token indices \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_T\). To prepare the data:

- Partition the dataset into subsequences of length \(n\).

- Introduce randomness by discarding \(d\) tokens at the beginning, where \(d \in [0, n)\).

- Create \(m = \lfloor (T - d) / n \rfloor\) subsequences: \(\mathbf{x}_d, \mathbf{x}_{d+n}, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_{d+n(m-1)}.\)

Each subsequence \(\mathbf{x}_t = [x_t, \ldots, x_{t+n-1}]\) serves as the input, and the target is the sequence shifted by one token: \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1} = [x_{t+1}, \ldots, x_{t+n}].\)

Before we move on, a summary, Language models estimate the joint probability of a text sequence. For long sequences, \(n\) - grams provide a convenient model by truncating the dependence. However, there is a lot of structure but not enough frequency to deal efficiently with infrequent word combinations via Laplace smoothing. Thus, we will focus on neural language modeling in subsequent sections. To train language models, we can randomly sample pairs of input sequences and target sequences in minibatches. After training, we will use perplexity to measure the language model quality.

Language models can be scaled up with increased data size, model size, and amount in training compute. Large language models can perform desired tasks by predicting output text given input text instructions.

With the background thoroghly introduced, let’s move on to Recurrent Neural Network. Please post any question you may have on piazza.